Frequently Asked Questions

Alternatively, feel free to inquire at mtbp@scilifelab.se.

What is the Molecular Tumor Board Portal (MTBP)?

The MTBP is a clinical decision support system that is employed in several ongoing

European clinical initiatives to share and harness tumor molecular data in the context of precision cancer medicine.

2. What is shown in the MTBP reports?

The report generated by the MTBP includes the following:

- clinical and sequencing information as available in the patient eCRF;

- which platform detected each genomic variant (e.g. whether a variant has been detected by the CCE panel in the germline vs somatic call, and/or by the FMI panel) and -in the case of mutations- at which variant allele frequency;

- evidences supporting the biological and clinical relevance of each variant according to state-of-the-art clinical and/or experimental and/or population studies, as well as computational analyses.

How is the MTBP report structured?

The MTBP report first shows clinical and sample data, including the tumor mutation burden and the

variant allele frequency histogram --which may be useful to assess sample purity and clonality--. Thereafter,

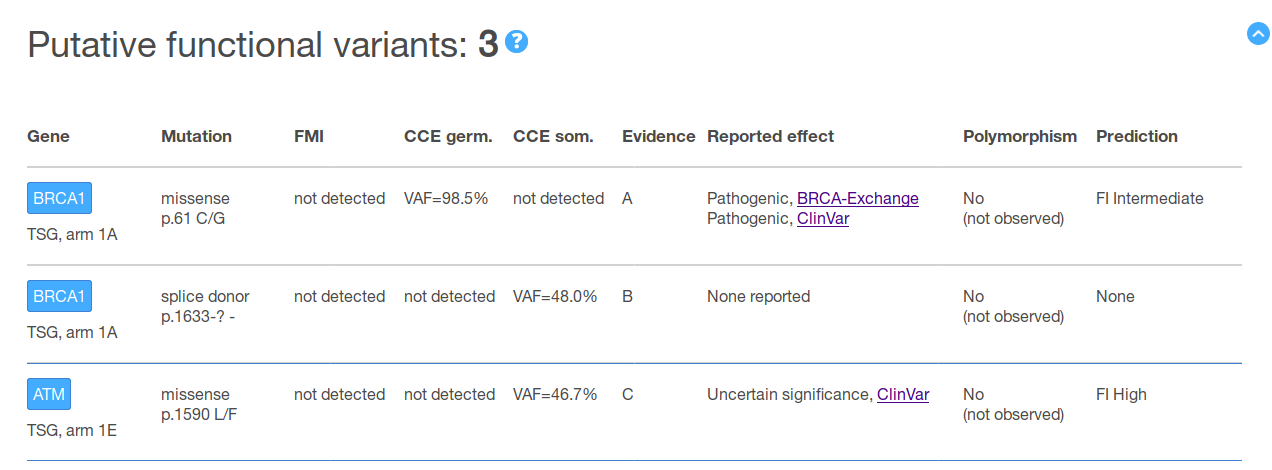

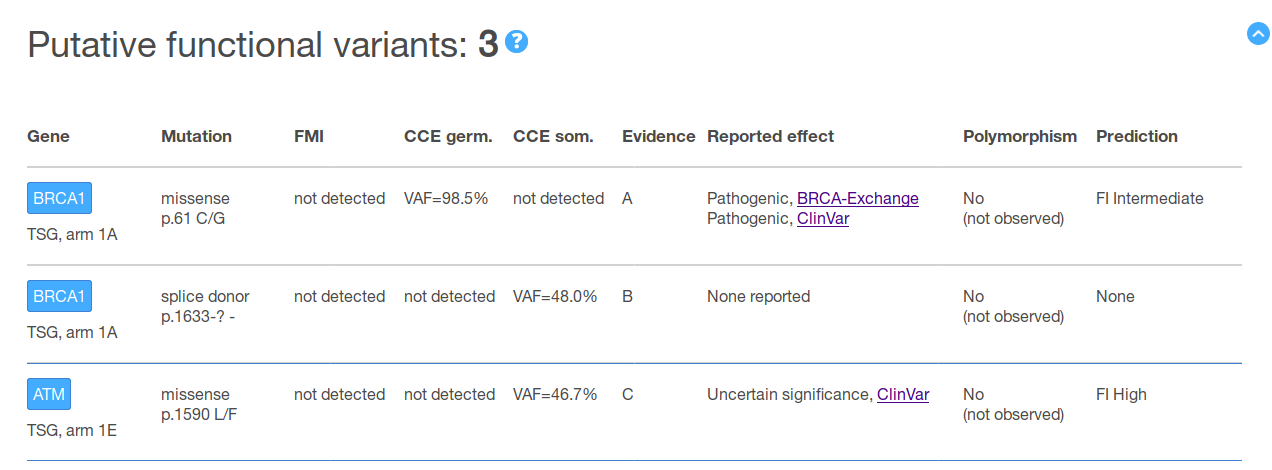

the report includes summary tables with an overview of the annotation retrieved for all the detected variants.

These tables separately show the variants that have been pre-classified as putative functional, putative neutral

and variants of unknown significance, respectively (see figure below as an example). An additional table with

the (oncogenic) copy number alterations that have been detected is also shown.

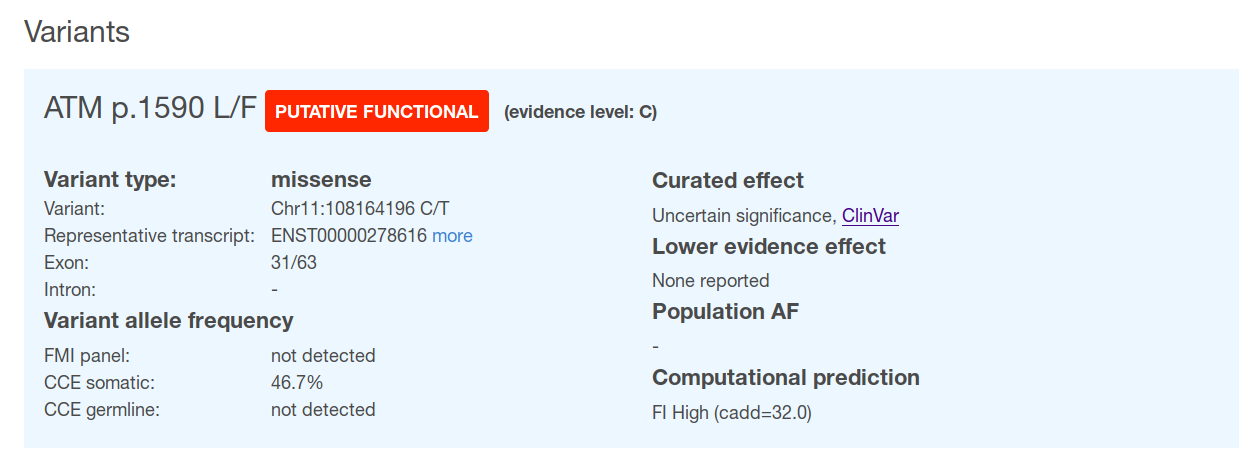

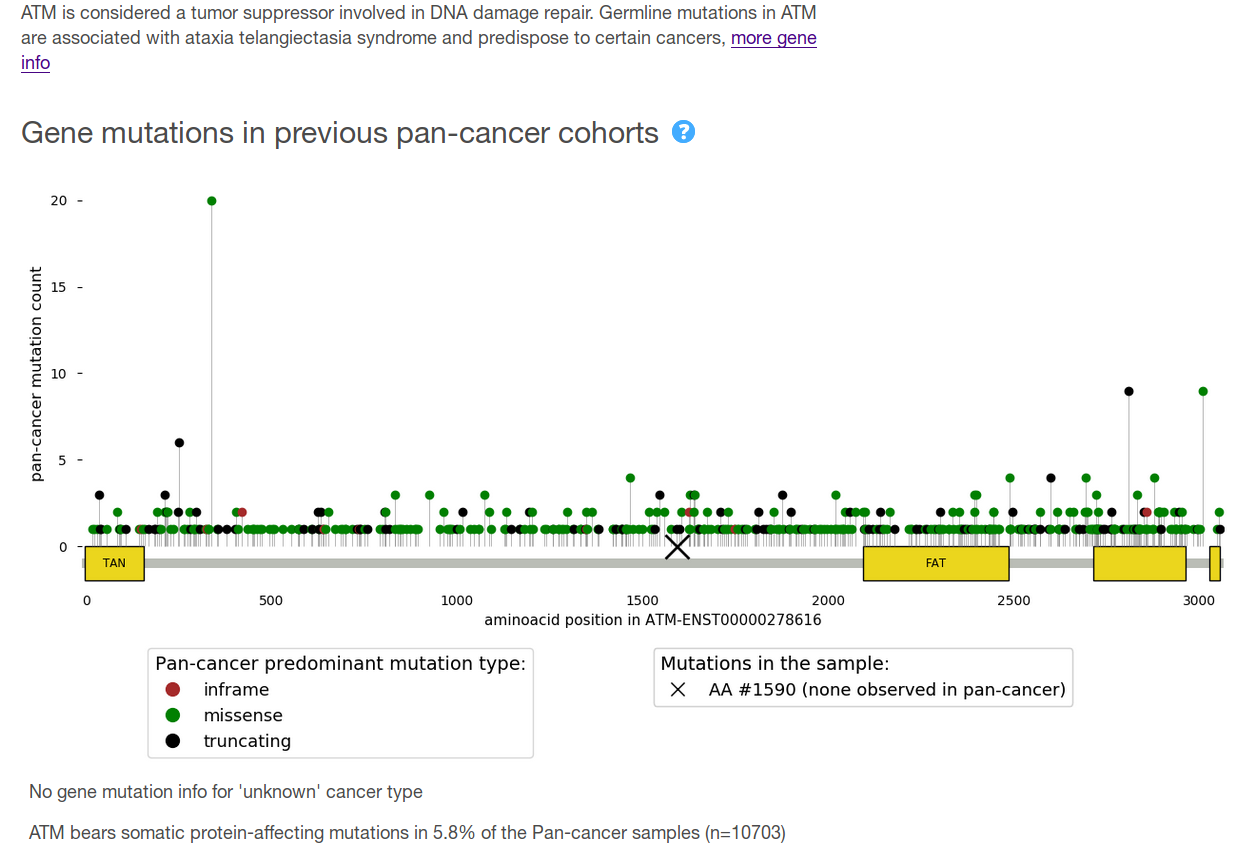

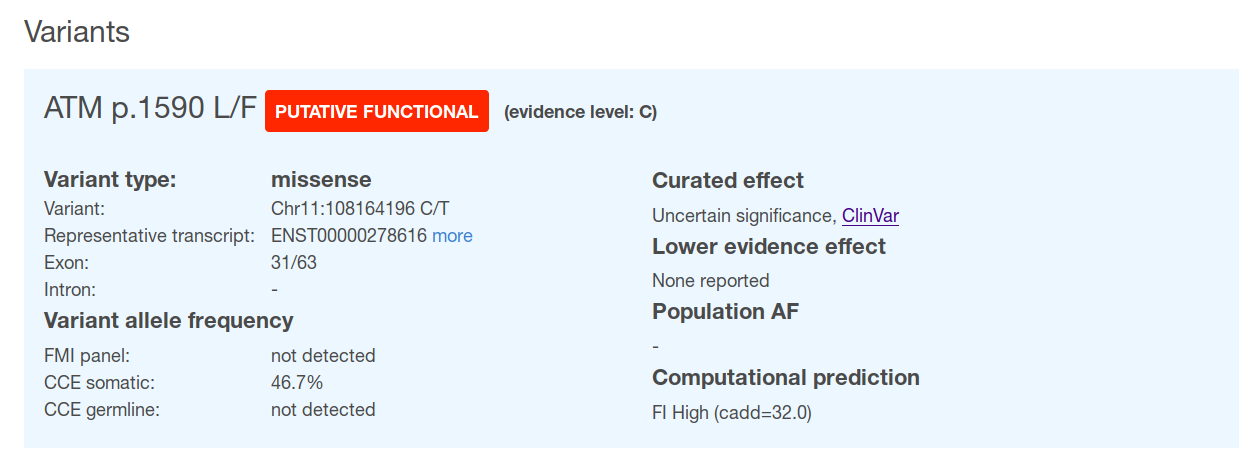

Finally, the report includes a detailed view with further information. On the one hand, and for each gene, the report provides (a) a brief description of its role in cancer; and (b) a comparison of the gene variants found in the sample with what has been observed across previously sequenced tumor cohorts. On the other, and at the level of each of the variants found in that gene, all the annotations included in the summary tables plus additional information --which is not considered relevant for variant classification but still of interest for a detailed review-- is shown (see figure below for example).

Finally, the report includes a detailed view with further information. On the one hand, and for each gene, the report provides (a) a brief description of its role in cancer; and (b) a comparison of the gene variants found in the sample with what has been observed across previously sequenced tumor cohorts. On the other, and at the level of each of the variants found in that gene, all the annotations included in the summary tables plus additional information --which is not considered relevant for variant classification but still of interest for a detailed review-- is shown (see figure below for example).

Are the BoB qualifying genes highlighted in the MTBP report?

Yes. In both the summary tables and in the gene variants detailed view, if the variant (or copy number alteration)

occurs in a gene that qualifies for a certain arm of the Basket of Baskets (BoB) clinical trial, this is flagged.

Does the report include information about the actionability for other gene alterations?

The tumor sample variants are matched with the information gathered in the different knowledgebases at the level of each

specific mutation (i.e. whether there is a reported effect for the particular variants found in the tumor sample). However, and

to evaluate off-label drug opportunities, it may be useful to also include the actionability of the gene for other variants than

those observed in the tumor sample. This may cover e.g. biomarkers of drug response that:

- are particular aminoacid changes different to that found in the tumor, but in which one may consider that they lead to a similar effect;

- are ‘regional’ biomarkers, as e.g. ‘mutations in exon 11 of gene X’, which the user can manually match with the information provided for the variant(s) found in that gene in the tumor; and

- are unespecific biomarkers, as e.g ‘oncogenic mutations in gene X’, which the user can pair with gene variants found in the tumor pre-classified as functional.

What is the format of the MTBP report?

The MTBP reports are in html format. This allows the user interaction through e.g. hovers/ pop-ups to better document the

report content, and the use of links to the external resources and original entries of each annotation. In addition, the MTBP provides

a ‘static’ version of the report in pdf format.

Are the reports generated by the original sources included in the MTBP?

The MTBP is prepared to include any document relevant for the patient sample, as far as it is transferred from the original

source. This may include e.g. the FMI pdf report, the CCE panel pdf report, or the ALEA pdf CRF.

3. Which knowledgebases are used to annotate the data?

BRCA Exchange aggregates large scale data about the BRCA1 and BRCA2

genes from different contributors. Therefore, public databases such as

ClinVar and LOVD are sources for the BRCA Exchange. For the MTBP reports,

only interpretations from the ENIGMA Expert Review panel are used. ENIGMA

(Evidence-based Network for the Interpretation of Germline Mutant Alleles) is an international consortium of researchers that provides

expert opinion on the clinical significance of variation in BRCA1, BRCA2, and other breast cancer genes. BRCA-Exchange uses standard terms

for clinical significance as recommended for germline variants by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association

for Molecular Pathology (ACMG/AMP), i.e. benign, likely benign, vus, pathogenic and likely pathogenic.

ClinVar is a public repository for the relationships among human variations and phenotypes. ClinVar does not manually review the content of each annotation but provides a quality score based on the information source. The MTBP reports considers only those assertions submitted by recognized expert panels and providers of clinical practice guidelines/recommendations, or by multiple submitters with concordant interpretations. The rest of the content in ClinVar is included in a separate section of the MTB report (detailed view) named ‘Lower evidence effect’, but this is not used as a source of primary annotation neither it contributes to the variants pre-classification. ClinVar uses standard terms to report the effect of germline variants as recommended by the ACMG/AMP, i.e. benign, likely benign, vus, pathogenic and likely pathogenic.

CIViC is a community-driven and expert-reviewed resource gathering clinical interpretations for cancer variants, including biomarkers of drug response, variants correlated with prognostic outcome or with diagnostic utility, and cancer predisposing variants. This knowledgebase contemplates also negative evidences. Each assertion is scored according to a trust rating based on the quality of the evidence (from one to five stars). The MTBP only considers those assertions with three or more stars; the rest of the content in CIViC is included in a separate section of the MTB variant report (detailed view) named ‘Lower evidence effect’, but this is not used as a source of primary annotation neither it contributes to the variants pre-classification. Variant interpretation is classified according to an in-house supporting evidence system (ranging from standard-of-care to investigational or hypothetical treatments).

OncoKB is a manually curated repository gathering knowledge about the biological and therapeutic effect of cancer gene alterations developed at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Variants with a reported effect in terms of their oncogenicity are classified as oncogenic, likely oncogenic, inconclusive and likely neutral. Variants shaping anti-cancer drugs outcome (i.e. response or resistance) are classified according to an in-house supporting evidence system (ranging from standard-of-care to inferential associations).

Cancer Genome Interpreter is a framework to identify the biological and clinical relevance of genomic alterations in cancer. For the latter, a database of genomic alterations shaping anti-cancer drug outcome (i.e. response, resistance or toxicity) curated and maintained by several clinical and scientific experts is employed. The level of evidence supporting the role of each biomarker is divided in 5 categories (following an equivalent system to that recommended by the ACMG/AMP somatic working group): a biomarker included in clinical guidelines/recommendations, a biomarker reported in late (phases III/IV) or early (phases I/II) stage clinical trials, a biomarker observed in (published) clinical case reports and a biomarker supported by preclinical data. This knowledgebase contemplates also negative evidences.

Of note, biomarkers of drug outcome gathered in parallel efforts are currently being integrated in a collaborative effort of the Global Alliance for Genomics and Health.

The 1000 Genomes Project gathers whole-genome sequencing data of 2,504 healthy individuals. The project followed a multi-sample approach combined with genotype imputation aimed to detect genetic variants with frequencies of at least 1% in the populations studied. On detail, 26 populations are included, divided into 5 ‘super populations’ (African, Ad Mixed American, East Asian, European and South Asian).

The Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) is a resource aggregating and harmonizing whole-exome and whole-genome sequencing data from large-scale sequencing projects (n=125,748 and 15,708 in the latest release, respectively). On detail, the project collects data from unrelated individuals sequenced as part of various disease-specific and population genetic studies, including normal samples from cancer patients. Individuals (and their first-degree relatives) known to be affected by severe pediatric diseases are removed from this dataset, but other individuals with severe disease as well as individuals with cancer predisposition can still be included in the data. Therefore, this dataset may be considered to estimate the allele frequency of variants in general population rather than healthy population. Data is divided into 7 ‘super populations’ (African/African American, American, Ashkenazi Jewish, East Asian, European (Finnish), European (non-Finnish), South Asian and Other).

ClinVar is a public repository for the relationships among human variations and phenotypes. ClinVar does not manually review the content of each annotation but provides a quality score based on the information source. The MTBP reports considers only those assertions submitted by recognized expert panels and providers of clinical practice guidelines/recommendations, or by multiple submitters with concordant interpretations. The rest of the content in ClinVar is included in a separate section of the MTB report (detailed view) named ‘Lower evidence effect’, but this is not used as a source of primary annotation neither it contributes to the variants pre-classification. ClinVar uses standard terms to report the effect of germline variants as recommended by the ACMG/AMP, i.e. benign, likely benign, vus, pathogenic and likely pathogenic.

CIViC is a community-driven and expert-reviewed resource gathering clinical interpretations for cancer variants, including biomarkers of drug response, variants correlated with prognostic outcome or with diagnostic utility, and cancer predisposing variants. This knowledgebase contemplates also negative evidences. Each assertion is scored according to a trust rating based on the quality of the evidence (from one to five stars). The MTBP only considers those assertions with three or more stars; the rest of the content in CIViC is included in a separate section of the MTB variant report (detailed view) named ‘Lower evidence effect’, but this is not used as a source of primary annotation neither it contributes to the variants pre-classification. Variant interpretation is classified according to an in-house supporting evidence system (ranging from standard-of-care to investigational or hypothetical treatments).

OncoKB is a manually curated repository gathering knowledge about the biological and therapeutic effect of cancer gene alterations developed at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Variants with a reported effect in terms of their oncogenicity are classified as oncogenic, likely oncogenic, inconclusive and likely neutral. Variants shaping anti-cancer drugs outcome (i.e. response or resistance) are classified according to an in-house supporting evidence system (ranging from standard-of-care to inferential associations).

Cancer Genome Interpreter is a framework to identify the biological and clinical relevance of genomic alterations in cancer. For the latter, a database of genomic alterations shaping anti-cancer drug outcome (i.e. response, resistance or toxicity) curated and maintained by several clinical and scientific experts is employed. The level of evidence supporting the role of each biomarker is divided in 5 categories (following an equivalent system to that recommended by the ACMG/AMP somatic working group): a biomarker included in clinical guidelines/recommendations, a biomarker reported in late (phases III/IV) or early (phases I/II) stage clinical trials, a biomarker observed in (published) clinical case reports and a biomarker supported by preclinical data. This knowledgebase contemplates also negative evidences.

Of note, biomarkers of drug outcome gathered in parallel efforts are currently being integrated in a collaborative effort of the Global Alliance for Genomics and Health.

The 1000 Genomes Project gathers whole-genome sequencing data of 2,504 healthy individuals. The project followed a multi-sample approach combined with genotype imputation aimed to detect genetic variants with frequencies of at least 1% in the populations studied. On detail, 26 populations are included, divided into 5 ‘super populations’ (African, Ad Mixed American, East Asian, European and South Asian).

The Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) is a resource aggregating and harmonizing whole-exome and whole-genome sequencing data from large-scale sequencing projects (n=125,748 and 15,708 in the latest release, respectively). On detail, the project collects data from unrelated individuals sequenced as part of various disease-specific and population genetic studies, including normal samples from cancer patients. Individuals (and their first-degree relatives) known to be affected by severe pediatric diseases are removed from this dataset, but other individuals with severe disease as well as individuals with cancer predisposition can still be included in the data. Therefore, this dataset may be considered to estimate the allele frequency of variants in general population rather than healthy population. Data is divided into 7 ‘super populations’ (African/African American, American, Ashkenazi Jewish, East Asian, European (Finnish), European (non-Finnish), South Asian and Other).

Is it the content of the knowledgebases processed somehow?

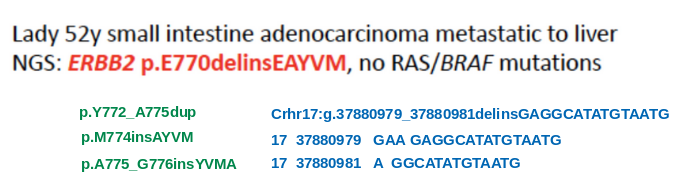

Each knowledgebase follows a disparate data model. A critical issue is the fact that distinct representation

may be employed for the same variant (e.g. different genomic coordinates syntax, or genomic vs protein coordinates) in each of them. In the following

example, the particular variant (in red) profiled in a given patient tumor can be found across knowledgebases in a variety of annotations in both protein

(green) and genomic (blue) coordinates (use case adapted from R.Dienstmann et al):

Therefore, the content of each knowledgebase needs to be harmonized to ensure cross-consistency.

Secondly, some of these knowledgebases include only those interpretations that comply with a certain quality criteria in their supporting evidences. However, others knowledgebases also includes assertions with supporting evidences of lower strength (e.g. studies that are not sufficiently powered, biomarkers with conflicting data, etc). The MTBP pipeline filters out the latter as appropriate, and these assertions are not used to pre-classify the variants. Of note, this information is still shown in a separate section (named Lower evidence) in the detailed view of the report for further evaluation.

Therefore, the content of each knowledgebase needs to be harmonized to ensure cross-consistency.

Secondly, some of these knowledgebases include only those interpretations that comply with a certain quality criteria in their supporting evidences. However, others knowledgebases also includes assertions with supporting evidences of lower strength (e.g. studies that are not sufficiently powered, biomarkers with conflicting data, etc). The MTBP pipeline filters out the latter as appropriate, and these assertions are not used to pre-classify the variants. Of note, this information is still shown in a separate section (named Lower evidence) in the detailed view of the report for further evaluation.

Where does the Tumor Mutation Burden information come from?

When Foundation Medicine panel data is transferred to the MTBP, the tumor mutation burden calculated by that test is included in the MTBP

summary report. For those cases in which Foundation Medicine can not calculate this parameter due to sample issues (e.g. sample contamination or tumor

purity), the value will appear as ‘unknown’.

Of note, the thresholds to classify the tumor mutation burden (TMB) in three categories used by conventional FMI reports are (at present): high (TMB >19.5 Muts/Mb), intermediate (5.5 Muts/Mb < TMB <19.5 Muts/Mb) and low (TMB <5.5 Muts/Mb). However, for the Cancer Core Europe BoB specifications, these thresholds are changed to high (TMB >16 Muts/Mb), intermediate (12 Muts/Mb< TMB <16 Muts/Mb) and low (TMB <12 Muts/Mb).

Of note, the thresholds to classify the tumor mutation burden (TMB) in three categories used by conventional FMI reports are (at present): high (TMB >19.5 Muts/Mb), intermediate (5.5 Muts/Mb < TMB <19.5 Muts/Mb) and low (TMB <5.5 Muts/Mb). However, for the Cancer Core Europe BoB specifications, these thresholds are changed to high (TMB >16 Muts/Mb), intermediate (12 Muts/Mb< TMB <16 Muts/Mb) and low (TMB <12 Muts/Mb).

How is the potential effect of a variant annotated?

Besides the variant annotation of its molecular consequence per transcript, the MTBP pipeline matches the sample variants with

state-of-the-art knowledge about:

This information is aggregated from different expert-curated databases devoted to gather information generated by clinical and/or experimental studies related to one or more of the aforementioned contexts, as well as sequencing results of healthy cohorts. Regarding the computational methods, only those demonstrating higher sensitivity (specificity) to predict functional (neutral) events are employed.

- the variant allele frequency across the healthy population;

- the variant pathogenicity (usually referring to the germline context);

- the variant oncogenicity (usually referring to the tumor somatic context);

- the value of the variant as a prognostic and/or diagnostic disease marker;

- the value of the variant as a biomarker of anti-cancer drug outcome (response, resistance and/or toxicity); and

- computational prediction of the effect of the variant in a particular cancer gene.

This information is aggregated from different expert-curated databases devoted to gather information generated by clinical and/or experimental studies related to one or more of the aforementioned contexts, as well as sequencing results of healthy cohorts. Regarding the computational methods, only those demonstrating higher sensitivity (specificity) to predict functional (neutral) events are employed.

Are the variants pre-classified?

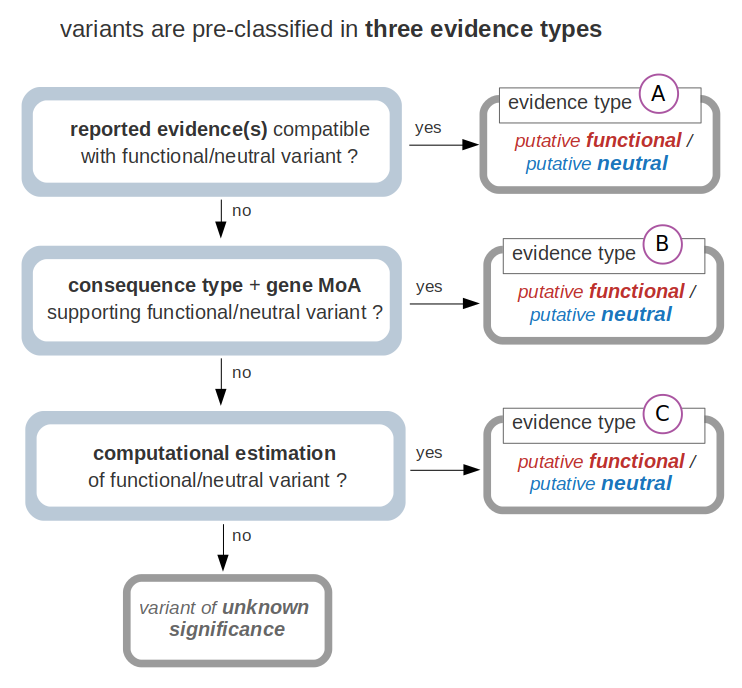

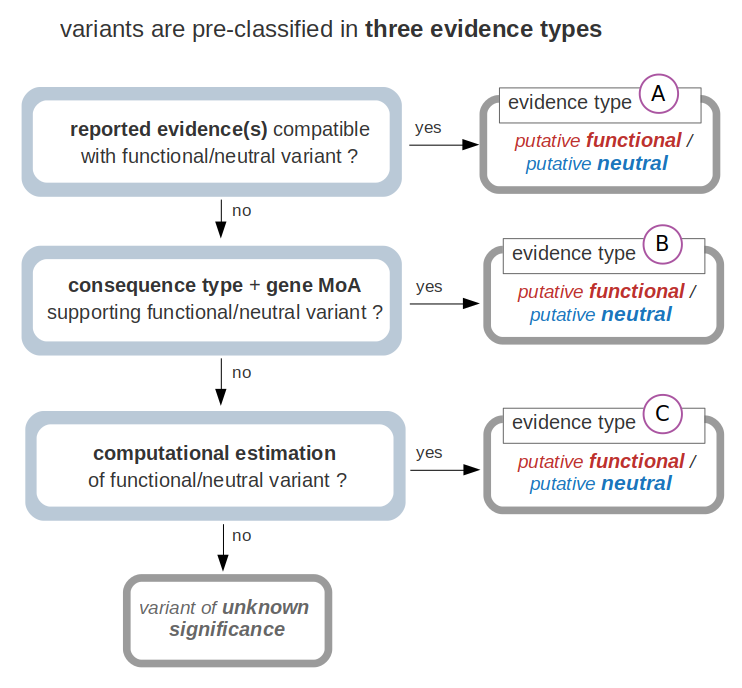

Yes, a classification of the variants following a predefined criteria is provided in the MTB summary report. On detail, ‘meta-categories’

that encompass any annotation compatible with a variant being putative functional or putative neutral -- or variant of unknown significance otherwise--

is employed. These categories should be taken as a guide and not --in any case-- as a final call. Indeed, the MTB summary report includes all the

ancillary data to empower the user’s review of these results. On detail, the variants are classified following the schema below:

Note that this classification follows a ‘hierarchical’ scheme. For instance, if a variant fulfills the condition(s) to be classified as putative functional with an evidence type A, whether it also fulfills the conditions for evidences B and/or C does not alter that classification statement.

Note that this classification follows a ‘hierarchical’ scheme. For instance, if a variant fulfills the condition(s) to be classified as putative functional with an evidence type A, whether it also fulfills the conditions for evidences B and/or C does not alter that classification statement.

How are the variants pre-classified as evidence type A?

Evidences of type A are determined for variants whose effect has been already reported in one (or more) of the

knowledgebases employed by the MTBP to annotate the data. These knowledgebases (detailed in a previous section) are the result of

several international efforts for gathering data provided by clinical, experimental and/or population studies. We have considered the knowledgebases

that comply with the following:

The sample variant can be classified as either putative functional or putative neutral - evidence type A when the effect of the variant reported in the knowledgebase(s) is ‘compatible’ with one of those two ‘meta-terms’. For instance, a variant associated with a certain germline cancer-predisposing syndrome and/or described to increase the sensitivity of tumor cells to a certain drug is supporting -in both cases-- that the variant is indeed functional. The mapping between the content of the knowledgebases employed by the MTBP and the classification given by the MTBP is the following:

If contradictory findings are reported for a variant (e.g. two knowledgebases report divergent effects), this event is flagged and the variant is classified as variant of unknown significance. Of note, as previously mentioned, some of these knowledgebases only include content that is backed by (what is considered) strong supporting data, whereas others collect also ‘lower quality evidences’. The MTB{} pipeline filters out the latter so only higher quality supporting data is employed for the variant classification.

- are expert curated;

- follow a transparent process to annotate the information;

- include reference(s) to the published evidences that support the assertions;

- are open for comments and review of the community; and

- update the content periodically.

The sample variant can be classified as either putative functional or putative neutral - evidence type A when the effect of the variant reported in the knowledgebase(s) is ‘compatible’ with one of those two ‘meta-terms’. For instance, a variant associated with a certain germline cancer-predisposing syndrome and/or described to increase the sensitivity of tumor cells to a certain drug is supporting -in both cases-- that the variant is indeed functional. The mapping between the content of the knowledgebases employed by the MTBP and the classification given by the MTBP is the following:

If contradictory findings are reported for a variant (e.g. two knowledgebases report divergent effects), this event is flagged and the variant is classified as variant of unknown significance. Of note, as previously mentioned, some of these knowledgebases only include content that is backed by (what is considered) strong supporting data, whereas others collect also ‘lower quality evidences’. The MTB{} pipeline filters out the latter so only higher quality supporting data is employed for the variant classification.

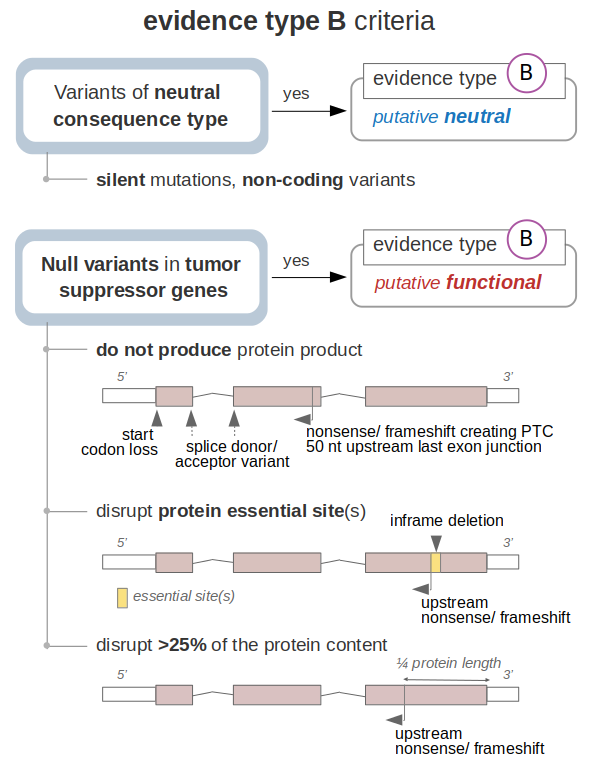

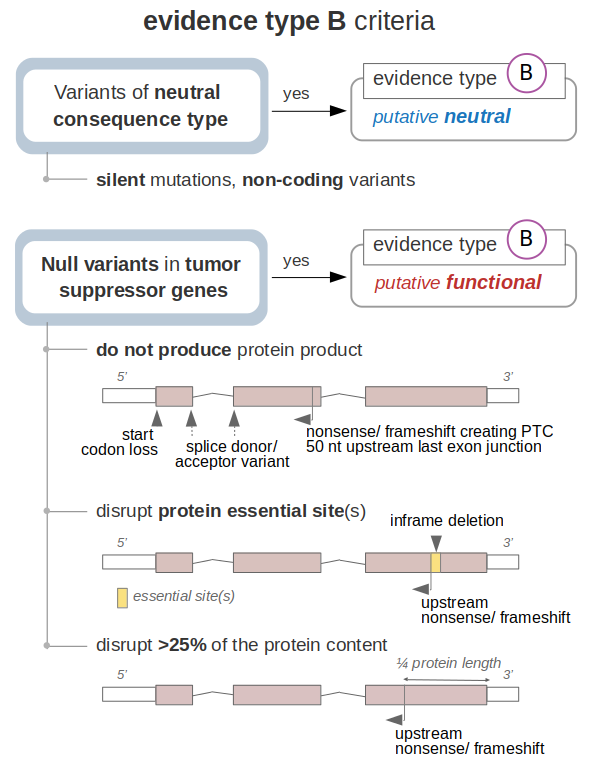

How are the variants pre-classified as evidence type B?

If the variant cannot be classified according to the previous criteria, the consequence type of the variant, its

location within the protein sequence and the mechanism of action of the gene in cancer is evaluated for

evidences of type B. The (predominant) mechanism of action (i.e. tumor suppressor or oncogene) is annotated according to manually

curated evidences (Cancer Gene Census, Sanger Institute) or according to a

computational estimation (20/20+, Tokhelm et al) as available. The criteria

to state evidences - type B are summarized in the following scheme:

On the one hand, variants that do not affect the coding sequence of the gene (and do not have any reported effect, which is covered in the evaluation of evidences- type A) are classified as putative neutral -evidence type B.

On the other, null variants that lead to the loss-of-function of a tumor suppressor according to bona fide criteria are classified as putative functional -evidence type B. This is stated under three main scenarios; first, variants that likely lead to the absence of the tumor suppressor gene product, which includes:

Note that variants leading to stop codon loss are not included among the above, since the effect of an elongated transcript is not assumed here.

Second, variants that do not fulfill the previous criteria but disrupt protein sites that are essential for the function of the tumor suppressor are also classified as putative functional - evidence type B. These essential sites are defined by the variants already reported to cause the loss-of-function of each protein (as gathered by the knowledgebases discussed in the previous sections). Disruption of these protein essential sites are assumed to equally lead to the loss-of-function of the tumor suppressor. This is stated in the following cases:

Note that inframe insertions are not included among the above, since the effect of inserting residues in essential site protein locations is not assumed here.

Finally, the remaining nonsense or frameshift variants that do not fulfill the previous criteria (i.e. they occur within the last exon of the transcript and downstream of any protein essential site) are evaluated depending on the portion of the protein that they affect. On detail, if the variant disrupts more than 25% of the tumor suppressor sequence (i.e. it is located upstream the ¾ of the transcript length), the variant is classified as putative functional. This figure is arbitrarily defined as the protein portion that when truncated or its sequence modified causes the loss-of-function of the encoded product.

Note again that these bona fide assumptions do not apply when the effect of the variant has been already reported as functional (e.g. nonsense variant APC: c.288T>G found to be pathogenic and thus classified as functional - evidence type A) or neutral (e.g. splice acceptor variant BRCA1:c.594-2A>C found to be benign/with little clinical significance and thus classified as neutral - evidence type A).

On the one hand, variants that do not affect the coding sequence of the gene (and do not have any reported effect, which is covered in the evaluation of evidences- type A) are classified as putative neutral -evidence type B.

On the other, null variants that lead to the loss-of-function of a tumor suppressor according to bona fide criteria are classified as putative functional -evidence type B. This is stated under three main scenarios; first, variants that likely lead to the absence of the tumor suppressor gene product, which includes:

- variants that disrupt the translation initiation codon;

- variants in the highly conserved donor GT or acceptor AG splice sites of the transcript; and

- nonsense variants or frameshift indels that create a premature stop codon more than 50 nucleotides upstream of the 3’-most exon-exon junction of the transcript (which likely triggers non-mediated decay mechanisms);

Note that variants leading to stop codon loss are not included among the above, since the effect of an elongated transcript is not assumed here.

Second, variants that do not fulfill the previous criteria but disrupt protein sites that are essential for the function of the tumor suppressor are also classified as putative functional - evidence type B. These essential sites are defined by the variants already reported to cause the loss-of-function of each protein (as gathered by the knowledgebases discussed in the previous sections). Disruption of these protein essential sites are assumed to equally lead to the loss-of-function of the tumor suppressor. This is stated in the following cases:

- nonsense or frameshift variants upstream of essential site(s) of a given protein, which consequently result truncated or its sequence modified. Of note, the essential sites considered here are those caused by missense variants and inframe indels as well as by nonsense and frameshift variants, which delimit specific residues and downstream regions that are essential for the protein function, respectively.

- inframe deletions intersecting protein essential sites which consequently result deleted. Of note, the essential sites considered here are only those caused by missense variants and inframe indels, which point out specific residues that are essential for the protein function.

Note that inframe insertions are not included among the above, since the effect of inserting residues in essential site protein locations is not assumed here.

Finally, the remaining nonsense or frameshift variants that do not fulfill the previous criteria (i.e. they occur within the last exon of the transcript and downstream of any protein essential site) are evaluated depending on the portion of the protein that they affect. On detail, if the variant disrupts more than 25% of the tumor suppressor sequence (i.e. it is located upstream the ¾ of the transcript length), the variant is classified as putative functional. This figure is arbitrarily defined as the protein portion that when truncated or its sequence modified causes the loss-of-function of the encoded product.

Note again that these bona fide assumptions do not apply when the effect of the variant has been already reported as functional (e.g. nonsense variant APC: c.288T>G found to be pathogenic and thus classified as functional - evidence type A) or neutral (e.g. splice acceptor variant BRCA1:c.594-2A>C found to be benign/with little clinical significance and thus classified as neutral - evidence type A).

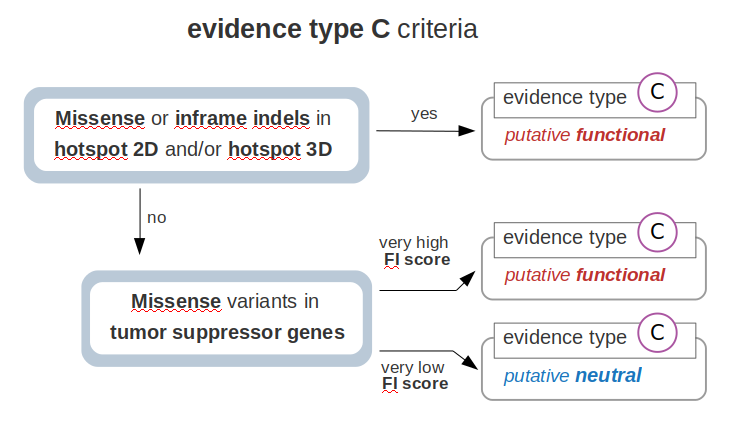

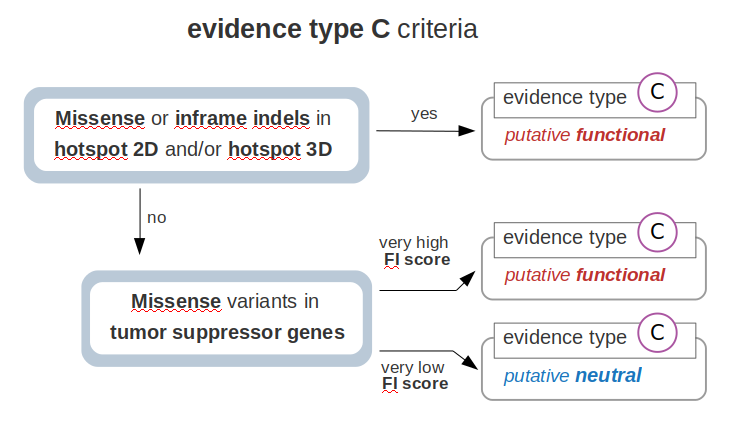

How are the variants pre-classified as evidence type C?

Finally, if the variant cannot be classified according to the previous criteria, further computational estimations are considered for

evidences of type C. These criteria are summarized in the following scheme:

First, if the sample variant occurs in a protein location identified as a hotspot of (somatic) mutations, the variant is classified as putative functional -evidence type C. Of note, missense variants and inframe indels are matched with hotspots driven by single nucleotide changes and inframe indels, respectively. Note that these hotspots are identified through the analysis of sequenced tumor cohorts data by methods that incorporate background mutation constraints. Thus,these hotspots are statistically significant findings and not a mere observation of variant spatial recurrence. The MTBP employs two methods to identify hotspots: one is the cancer hotspots algorithm developed by Chang el al, which identifies hotspots in the protein lineal sequence of each gene; and the other is the cancer 3D hotspots algorithm developed by Gao et al, which considers residues that are close in the three-dimensional protein structure space.

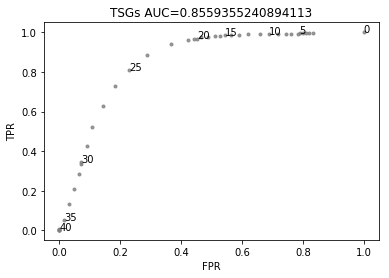

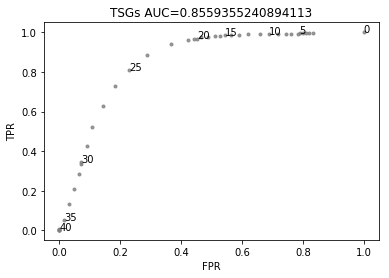

Second, those variants that do not fulfill any of the previous criteria are further evaluated by their estimated functional impact (FI). Only missense variants are included here, since the relevance of variants of null consequence types is covered by the previous assessments. We benchmarked the performance of different FI scores by using the catalog of variants already known to be functional and neutral (as gathered by the knowledgebases employed by the MTBP). As expected, these methods show a better performance to identify missense variants that are biologically relevant in tumor suppressors than in oncogenes. As described elsewhere, this is partially explained by the fact that these methods rely in measurements (e.g. conservation scores) that better detect loss-of-function events as compared to gain-of-function events. Therefore, the MTBP pipeline uses the FI score to evaluate the relevance of missense variants only in tumor suppressor genes. For this aim, the Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD) score showed the best overall performance (data not shown). This method integrates multiple annotations --via a support vector machine approach-- into one metric aimed to estimate the deleteriousness of a variant (see Kircher et al for more details). In our benchmarking, CADD obtains an area under the curve of 0.85 to discriminate missense variants in tumor suppressors known to be functional and neutral, respectively (see figure below). The MTBP pipeline uses stringent cutoffs to classify the variants: on the one hand, missense variants with a CADD Phred score >30 in tumor suppressors are classified as putative functional. This cutoff is estimated to retrieve only a ~6% of false positives (see figure below). On the other, missense variants with a CADD Phred score < 20 are classified as putative neutral. This cutoff is estimated to retrieve a 95% of true negatives (see figure below).

First, if the sample variant occurs in a protein location identified as a hotspot of (somatic) mutations, the variant is classified as putative functional -evidence type C. Of note, missense variants and inframe indels are matched with hotspots driven by single nucleotide changes and inframe indels, respectively. Note that these hotspots are identified through the analysis of sequenced tumor cohorts data by methods that incorporate background mutation constraints. Thus,these hotspots are statistically significant findings and not a mere observation of variant spatial recurrence. The MTBP employs two methods to identify hotspots: one is the cancer hotspots algorithm developed by Chang el al, which identifies hotspots in the protein lineal sequence of each gene; and the other is the cancer 3D hotspots algorithm developed by Gao et al, which considers residues that are close in the three-dimensional protein structure space.

Second, those variants that do not fulfill any of the previous criteria are further evaluated by their estimated functional impact (FI). Only missense variants are included here, since the relevance of variants of null consequence types is covered by the previous assessments. We benchmarked the performance of different FI scores by using the catalog of variants already known to be functional and neutral (as gathered by the knowledgebases employed by the MTBP). As expected, these methods show a better performance to identify missense variants that are biologically relevant in tumor suppressors than in oncogenes. As described elsewhere, this is partially explained by the fact that these methods rely in measurements (e.g. conservation scores) that better detect loss-of-function events as compared to gain-of-function events. Therefore, the MTBP pipeline uses the FI score to evaluate the relevance of missense variants only in tumor suppressor genes. For this aim, the Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD) score showed the best overall performance (data not shown). This method integrates multiple annotations --via a support vector machine approach-- into one metric aimed to estimate the deleteriousness of a variant (see Kircher et al for more details). In our benchmarking, CADD obtains an area under the curve of 0.85 to discriminate missense variants in tumor suppressors known to be functional and neutral, respectively (see figure below). The MTBP pipeline uses stringent cutoffs to classify the variants: on the one hand, missense variants with a CADD Phred score >30 in tumor suppressors are classified as putative functional. This cutoff is estimated to retrieve only a ~6% of false positives (see figure below). On the other, missense variants with a CADD Phred score < 20 are classified as putative neutral. This cutoff is estimated to retrieve a 95% of true negatives (see figure below).

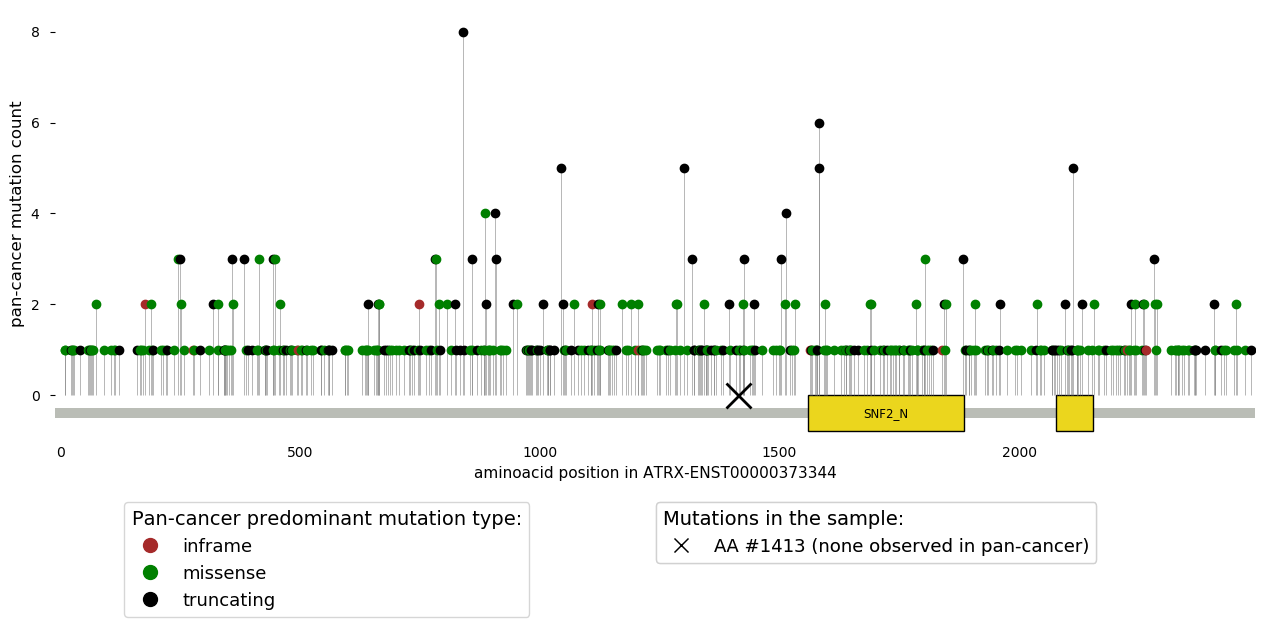

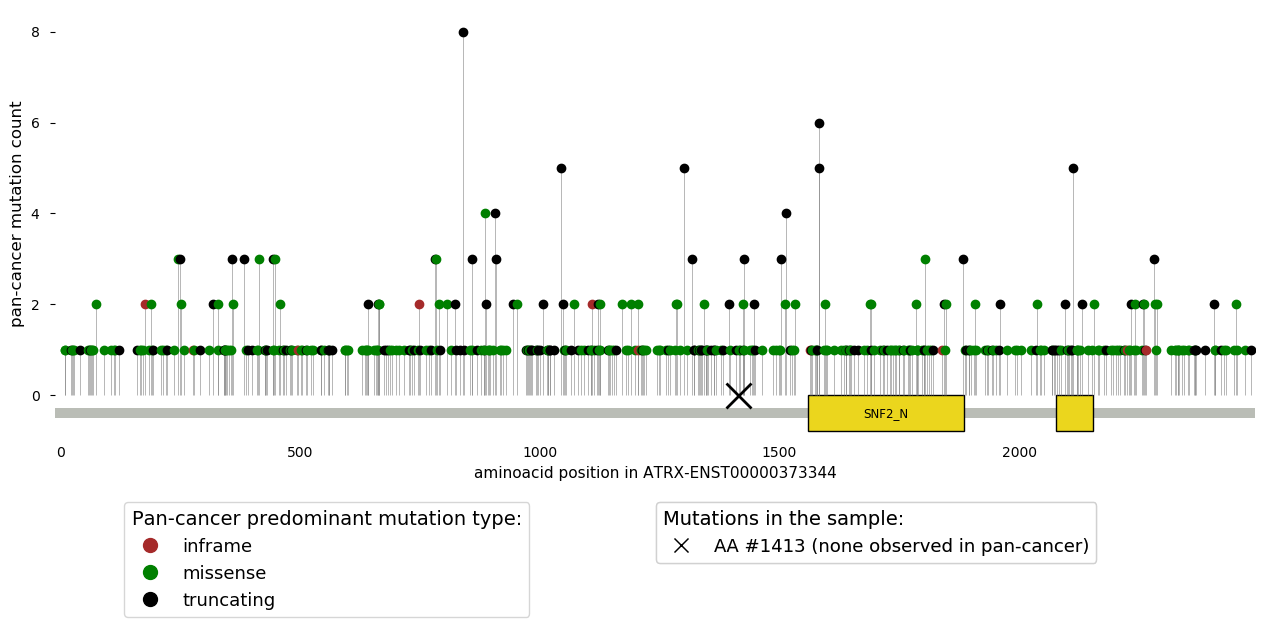

Are the variants of the sample compared with previous tumor cohorts?

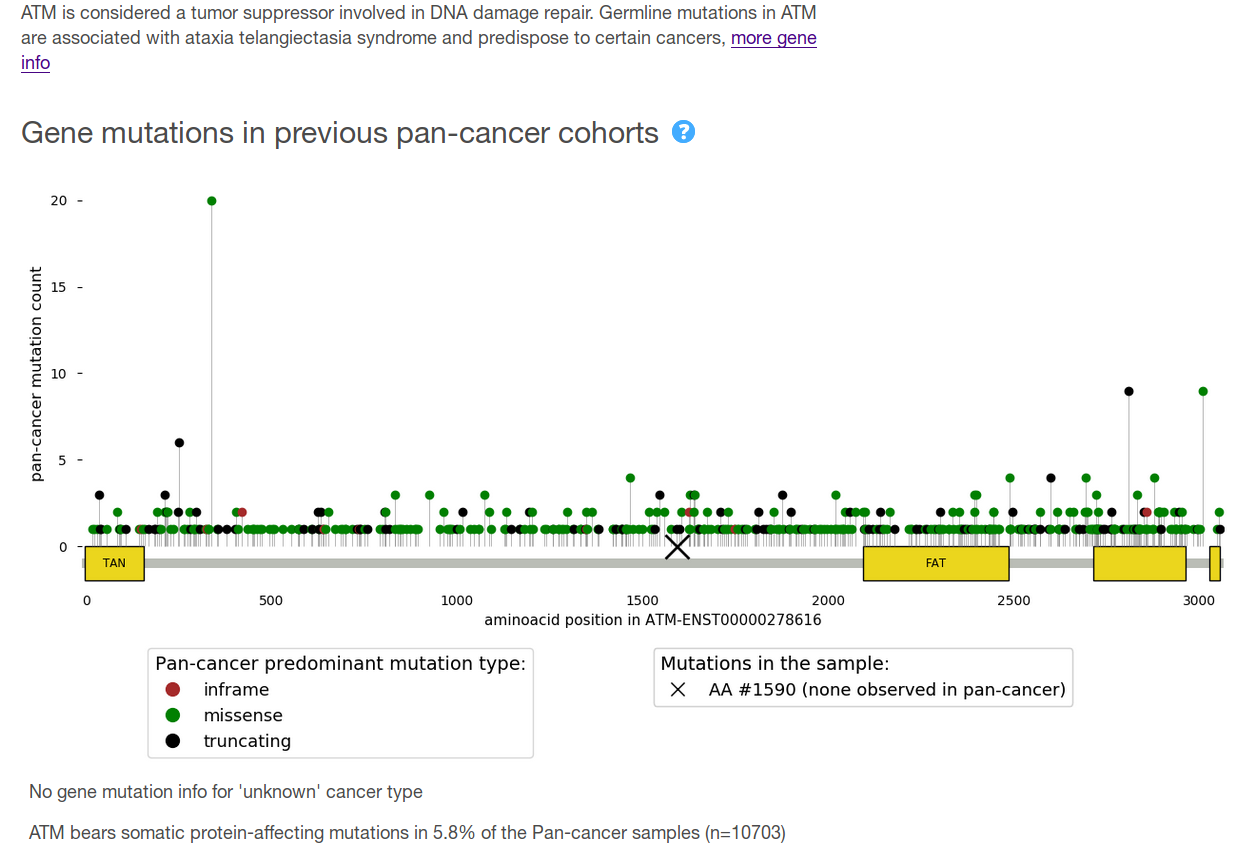

Variants observed in the analysed sample are compared with those of a

pan-cancer cohort of more than 10,000 advanced tumor patients profiled by the

MSK-IMPACT panel. On detail, the following information is provided:

Of note, these data is aimed for descriptive purposes and this information is not used to classify the tumor variants.

- The frequency of protein-affecting mutations observed in the gene in which the variant is observed. The frequency across the whole pan-cancer cohort and across tumors of same the cancer type than that of the sample under analysis (using the level 2 of the Oncotree taxonomy) is given. Note that for the latter, the given cancer type for the analysed sample is walked through the taxonomy as appropriate to reach that level 2.

- Location of the mutation in the encoded protein as compared to those observed across the >10,000 pan-cancer cohort (see figure above). Note that if the observed mutation is not exonic (and thus not in the protein sequence), this will not appear in that scheme. The color of the needles represents the mutation type that is more frequently observed in that protein position across the pan-cancer cohort. The domains of the protein are represented by yellow boxes, with their Pfam acronym displayed as possible.

Of note, these data is aimed for descriptive purposes and this information is not used to classify the tumor variants.

Security and backup policy

The MTBP complies with the technical and legal requirements of the GDPR regulation & Patient Data Laws, including the following:

- access to the MTBP is restricted to the involved parties by allowing only pre-approved IP addresses;

- only http and https network protocols are opened in the server (http requests will be directed to https); sftp is also used for the transfer of data from specific sources;

- the server is accessible from the internal network to only 2-5 internal nodes of the Karolinska Institutet environment using SSH protocol;

- usage and access to the system is defined by a user-centric permission system;

- attempts to log in will be limited to 5 before the account is locked;

- login credentials have a complex password policy with a two-factor authentication (by using the user’s email);

- access to the portal is granted upon acceptance of a user consent (which includes the terms for a responsible data usage) provided in the first use of the system;

- actions of the users in the portal are stored in the system;

- files uploaded to the MTBP are scanned for viruses before processing them;

- common security vulnerabilities such as SQL injection and session management are addressed in the system design;

- backup of the web application, repository files and analyses are performed once per day.

Updates policy

The portal will be updated in a regular basis to address three issues: (a) updates in the knowledgebases already used in the MTBP pipeline;

(b) addition of methods/knowledgebases to improve the annotations already in place; and (c) inclusion of new features that may raise as of interest.

The link(s) to the original source entry for each corresponding annotation is provided in the report. In addition, the MTBP pipeline follows a version control that tracks the version of each knowledgebase/method employed for the analyses.

The link(s) to the original source entry for each corresponding annotation is provided in the report. In addition, the MTBP pipeline follows a version control that tracks the version of each knowledgebase/method employed for the analyses.

Terms and conditions

The MTBP is intended to support the interpretation of molecular tumor data. This must not substitute a doctor’s medical judgement or

healthcare professional advice.

The MTBP uses several external tools and databases that are free for non-commercial use but restrict any distribution with commercial purposes. Therefore, the results of the MTBP must be used only with research purposes and must credit the original sources as appropriate.

The MTBP uses several external tools and databases that are free for non-commercial use but restrict any distribution with commercial purposes. Therefore, the results of the MTBP must be used only with research purposes and must credit the original sources as appropriate.

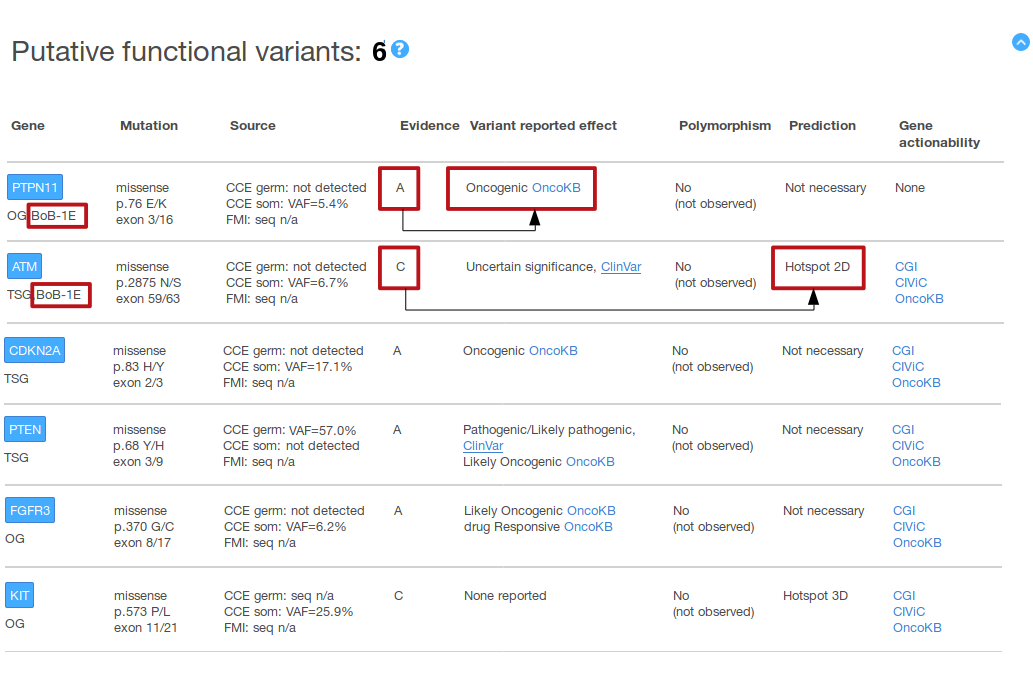

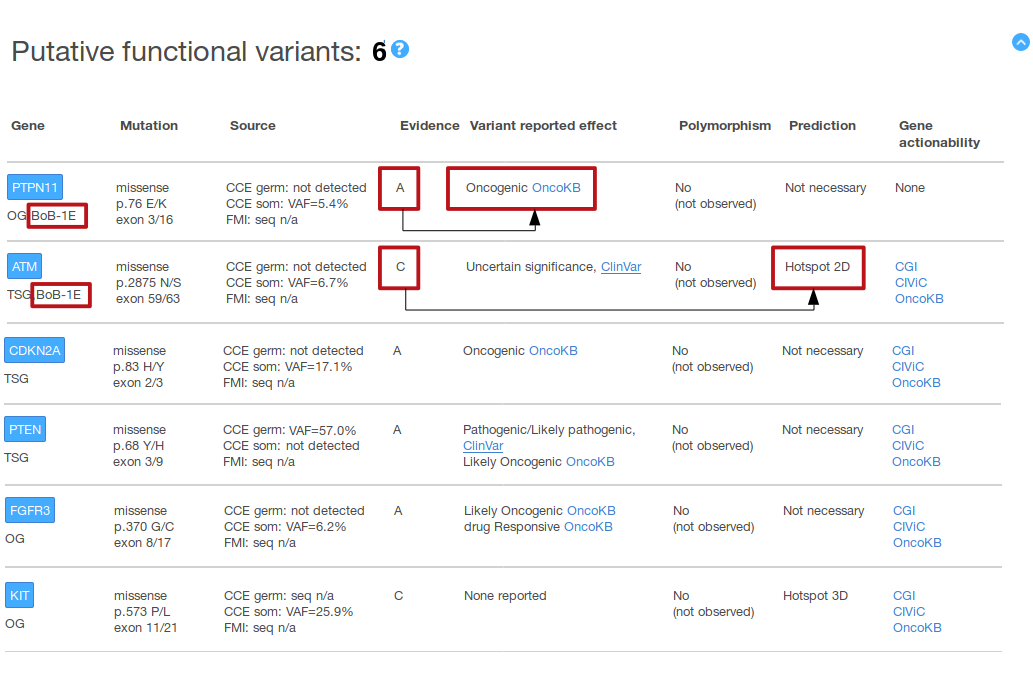

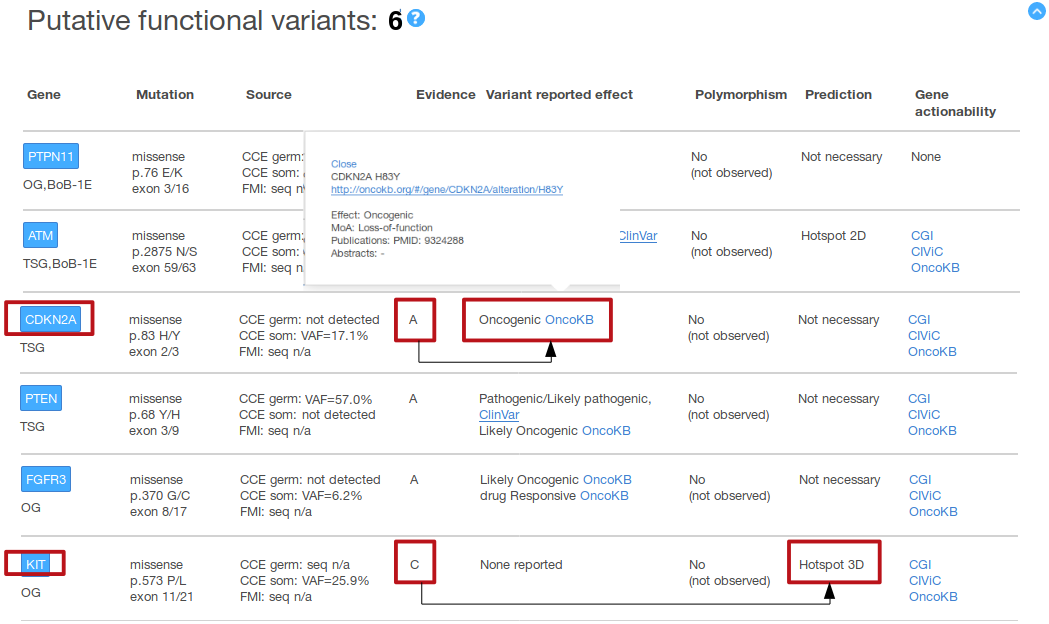

Use case 1: allocation of patients to BoB

To support the allocation of patients to BoB, search for variants in genes qualifying for BoB arms, which (if any) are shown first in the

MTBP summary tables. Note that the label ‘BoB’ is displayed under the gene symbol together with the corresponding BoB arm to facilitate this process

(see figure below).

Likely, those variants pre-classified as putative functional should be prioritized, although we encourage to (a) review the supporting evidence(s) to state that effect for any of the three levels of evidence (i.e. A, B or C); and (b) to also take into consideration other variants in these genes that may appear pre-classified as variants of unknown significance and/or putative neutral variants.

In the above example, two variants in BoB qualifying genes (both from the arm 1E) appear at the beginning of the ‘Putative functional variants’ summary table. The functional effect of one (PTPN11 p.76 E/K) is supported by an evidence A, i.e. the effect has been reported in a knowledgebase (is an oncogenic variant according to OncoKB); the functional effect of the other variant (ATM p.2875 N/S) is supported by an evidence C, i.e. a computational analysis (the variant occurs in a pre-identified hotspot of somatic mutations in the ATM protein 2D sequence).

Likely, those variants pre-classified as putative functional should be prioritized, although we encourage to (a) review the supporting evidence(s) to state that effect for any of the three levels of evidence (i.e. A, B or C); and (b) to also take into consideration other variants in these genes that may appear pre-classified as variants of unknown significance and/or putative neutral variants.

In the above example, two variants in BoB qualifying genes (both from the arm 1E) appear at the beginning of the ‘Putative functional variants’ summary table. The functional effect of one (PTPN11 p.76 E/K) is supported by an evidence A, i.e. the effect has been reported in a knowledgebase (is an oncogenic variant according to OncoKB); the functional effect of the other variant (ATM p.2875 N/S) is supported by an evidence C, i.e. a computational analysis (the variant occurs in a pre-identified hotspot of somatic mutations in the ATM protein 2D sequence).

Use case 1b: prioritization of BoB module 1 arms

In case that alterations qualifying for more than one BoB arms are observed in the tumor, the allocation of the patient to a particular

arm should follow the following hierarchy:

- arm 1F: CD274 amplification

- arm 1A: putative functional variants in BRCA1 and/or BRCA2

- arm 1B: putative functional variants in MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and/or PMS2

- arm 1C: putative functional variants in POLE and/or POLD1

- arm 1D: high tumor mutation burden

- arm 1E: putative functional variants in any of the DNA damage genes of that arm

Use case 2: allocation of patients to other clinical trials

Variants in genes that qualify for other genomic-guided clinical trials can be also checked in the MTBP report. For those cases in which

the inclusion criteria is a specific variant (e.g. BRAF p.600 V/E), the report does not provide any info of interest beyond the fact of whether the

variant has been found or not in the tumor sample. However, for those cases in which the inclusion criteria is loose (e.g. FGFR3 ‘oncogenic mutations’,

or ‘PTEN loss-of-function’), the pre-classification of variants into putative functional, putative neutral or VUS categories supports the interpretation

of any variant found in the gene(s) of interest.

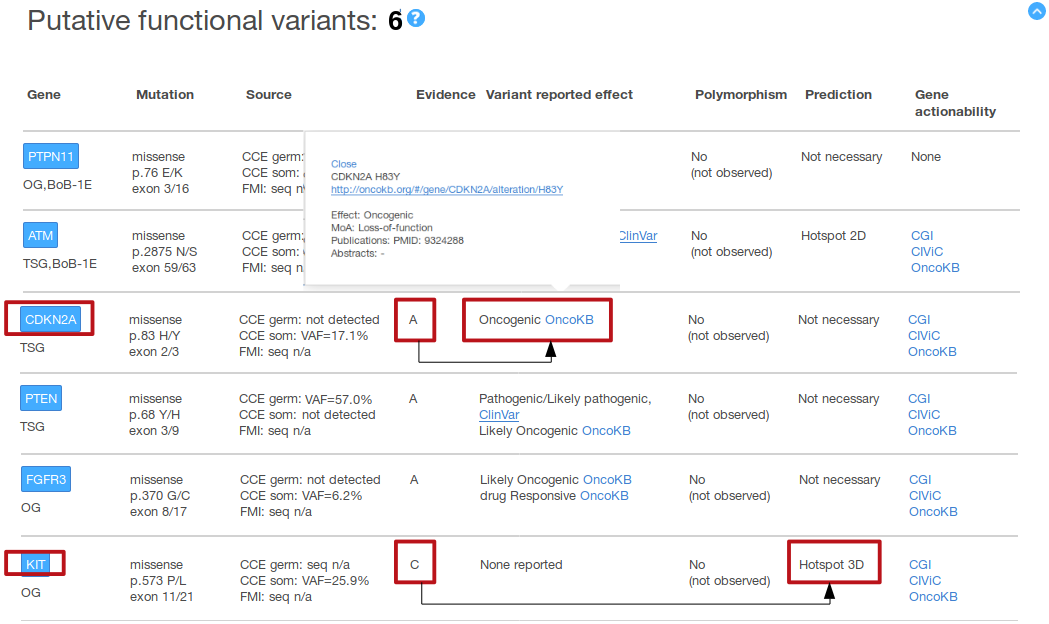

For this example, we suppose that there are two ongoing clinical trials in which the inclusion criteria is the presence of functional mutations in

CDKN2A and of functional mutations in KIT, respectively (without any particular mutation type further specified). In the figure above, we can see in

the ‘Putative functional variants’ summary table that variants pre-classified as putative functional are observed for both genes, which points out

that the patient may be a good candidate for both clinical trials. On detail, this example shows a CDKN2A variant (p.83 H/Y) pre-classified as

functional according to the knowledgebases data, i.e. evidence A (oncogenic according to OncoKB in that example); and a KIT mutation (p.573 P/L)

supported as functional according to computational analyses, i.e. evidence C (the variant occurs in a pre-identified hotspot of somatic mutations

in the KIT protein 3D structure in that example). In the figure above we also display the popup with the digested OncoKB information for CDKN2A

H83Y, including the link to the variant entry in the original source.

For this example, we suppose that there are two ongoing clinical trials in which the inclusion criteria is the presence of functional mutations in

CDKN2A and of functional mutations in KIT, respectively (without any particular mutation type further specified). In the figure above, we can see in

the ‘Putative functional variants’ summary table that variants pre-classified as putative functional are observed for both genes, which points out

that the patient may be a good candidate for both clinical trials. On detail, this example shows a CDKN2A variant (p.83 H/Y) pre-classified as

functional according to the knowledgebases data, i.e. evidence A (oncogenic according to OncoKB in that example); and a KIT mutation (p.573 P/L)

supported as functional according to computational analyses, i.e. evidence C (the variant occurs in a pre-identified hotspot of somatic mutations

in the KIT protein 3D structure in that example). In the figure above we also display the popup with the digested OncoKB information for CDKN2A

H83Y, including the link to the variant entry in the original source.

For this example, we suppose that there are two ongoing clinical trials in which the inclusion criteria is the presence of functional mutations in

CDKN2A and of functional mutations in KIT, respectively (without any particular mutation type further specified). In the figure above, we can see in

the ‘Putative functional variants’ summary table that variants pre-classified as putative functional are observed for both genes, which points out

that the patient may be a good candidate for both clinical trials. On detail, this example shows a CDKN2A variant (p.83 H/Y) pre-classified as

functional according to the knowledgebases data, i.e. evidence A (oncogenic according to OncoKB in that example); and a KIT mutation (p.573 P/L)

supported as functional according to computational analyses, i.e. evidence C (the variant occurs in a pre-identified hotspot of somatic mutations

in the KIT protein 3D structure in that example). In the figure above we also display the popup with the digested OncoKB information for CDKN2A

H83Y, including the link to the variant entry in the original source.

For this example, we suppose that there are two ongoing clinical trials in which the inclusion criteria is the presence of functional mutations in

CDKN2A and of functional mutations in KIT, respectively (without any particular mutation type further specified). In the figure above, we can see in

the ‘Putative functional variants’ summary table that variants pre-classified as putative functional are observed for both genes, which points out

that the patient may be a good candidate for both clinical trials. On detail, this example shows a CDKN2A variant (p.83 H/Y) pre-classified as

functional according to the knowledgebases data, i.e. evidence A (oncogenic according to OncoKB in that example); and a KIT mutation (p.573 P/L)

supported as functional according to computational analyses, i.e. evidence C (the variant occurs in a pre-identified hotspot of somatic mutations

in the KIT protein 3D structure in that example). In the figure above we also display the popup with the digested OncoKB information for CDKN2A

H83Y, including the link to the variant entry in the original source. Use case 3: off-label drug opportunities

State-of-the-art knowledge about the effect(s) of genomic variants that are already reported is employed by the MTBP pipeline to pre-classify

the tumor sample variants as putative functional and/or putative neutral. This includes information of their relevance as a biomarker of drug outcome

(i.e. their ability to shape the drug response, resistance and/or toxicity). Of note, the observation of these variants in the ‘Variant reported

effect’ column of the ‘Putative functional variants’ table may support off-label drug opportunities. By clicking in the corresponding entry, we show

a digested summary of this information; the link to the original source, where all the details can be checked, is also included there (see figure below).

In the figure above, three variants in three genes (PDGFRA, RET and SMO) are identified as biomarkers of drug response according to different knowledgebases (which make these variants to be pre-classified as putative functional, evidence A, in our report). We also show in that figure the popups with the digested information that appears for the CIViC entry PDGFRA p.674T/I (in the context of FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion) and for the CGI entry SMO p.535 W/L, respectively. Note that the link to the variant entry in the original source is also included in the popup. In addition, note that the column ‘Gene actionability’ displays a general summary of the landscape of actionability (if any) reported for any alteration in the gene as described by the different knowledgebases. In the popup that is opened when clicking in the corresponding entry, we show which gene alterations have been described as drug biomarker and include the link to the gene view in the original resource. In the figure above, we display the popup of the gene actionability for RET according to OncoKB.

Three knowledgebases are aggregated in the MTBP pipeline to discover biomarkers of drug response (see the FAQ Which knowledgebases are used? for more info): CIViC, OncoKB (actionability database) and Cancer Genome Interpreter (biomarkers database). Of note, incoming releases of the portal may include a report section specifically designed to communicate anti-cancer drug opportunities.

In the figure above, three variants in three genes (PDGFRA, RET and SMO) are identified as biomarkers of drug response according to different knowledgebases (which make these variants to be pre-classified as putative functional, evidence A, in our report). We also show in that figure the popups with the digested information that appears for the CIViC entry PDGFRA p.674T/I (in the context of FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion) and for the CGI entry SMO p.535 W/L, respectively. Note that the link to the variant entry in the original source is also included in the popup. In addition, note that the column ‘Gene actionability’ displays a general summary of the landscape of actionability (if any) reported for any alteration in the gene as described by the different knowledgebases. In the popup that is opened when clicking in the corresponding entry, we show which gene alterations have been described as drug biomarker and include the link to the gene view in the original resource. In the figure above, we display the popup of the gene actionability for RET according to OncoKB.

Three knowledgebases are aggregated in the MTBP pipeline to discover biomarkers of drug response (see the FAQ Which knowledgebases are used? for more info): CIViC, OncoKB (actionability database) and Cancer Genome Interpreter (biomarkers database). Of note, incoming releases of the portal may include a report section specifically designed to communicate anti-cancer drug opportunities.

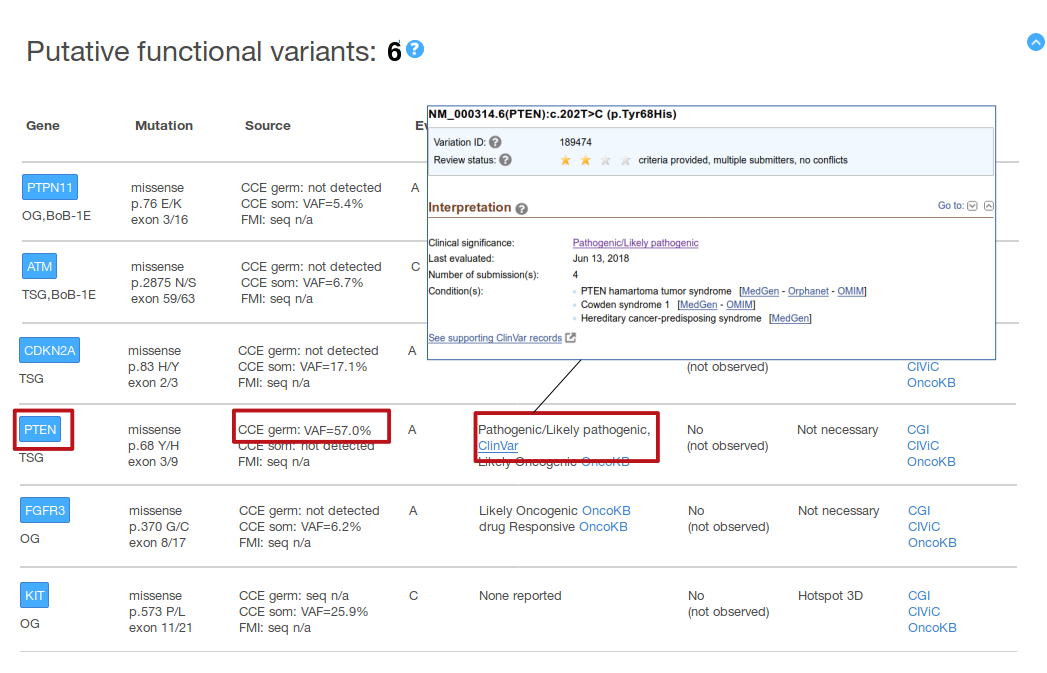

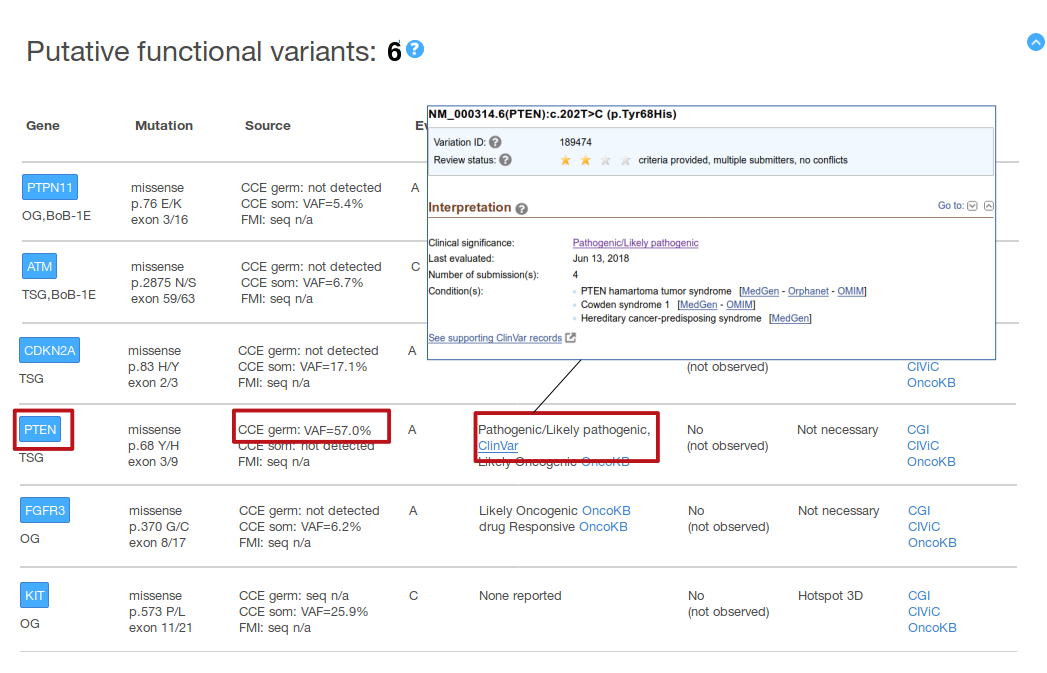

Use case 4: genomic counseling

State-of-the-art knowledge about the effect(s) of genomic variants that are already reported is employed by the MTBP pipeline to

pre-classify the tumor sample variants as putative functional and/or putative neutral. This includes information of pathogenicity, i.e. whether a

germline variant has been reported to cause (or predispose to) a certain disease. The observation of variants that are germline (or that cannot

be discarded to be) labelled as ‘pathogenic’ / ‘likely pathogenic’ in the ‘reported effect’ column point out cases in which genomic counseling

may be indicated (see figure below).

In the above figure, PTEN p.68 Y/H variant is found in the CCE panel, germline call (VAF=57%). This variant is described as Pathogenic/Likely Pathogenic by ClinVar (which makes the variant to be pre-classified as putative functional, evidence A, in our report). By clicking in that entry, the original ClinVar entry will be opened in a new browser tab (shown in the figure above: an interpretation agreed across several ClinVar submitters --see the two stars on top-- for the germline variant causing three different conditions --as last reviewed in June 13, 2018--).

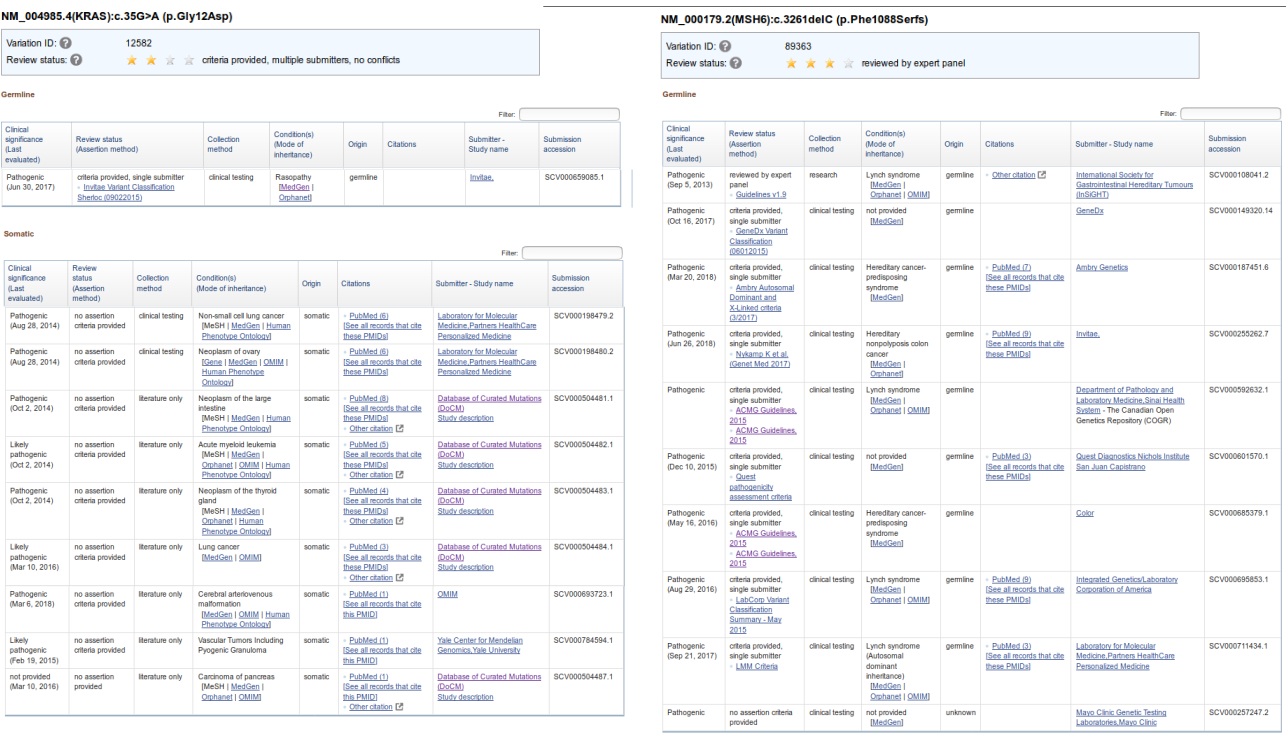

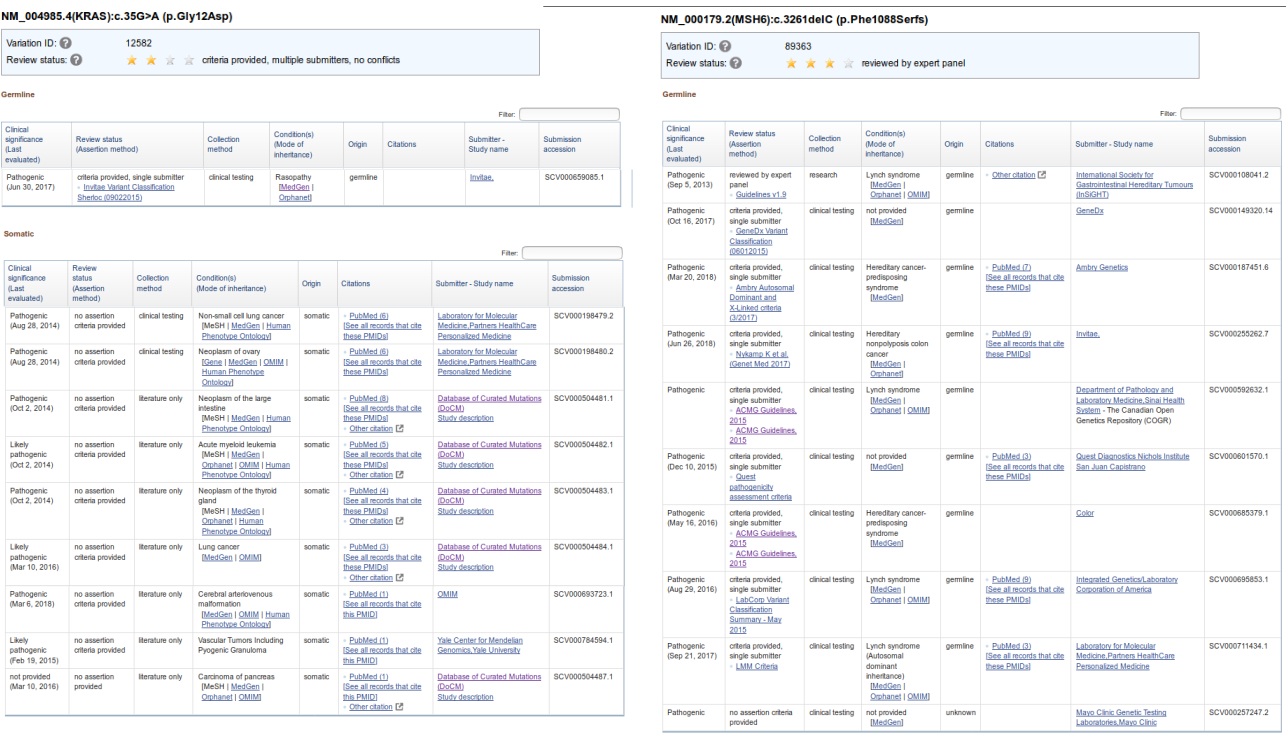

Of note, not all the variants labeled as pathogenic (or likely pathogenic) correspond to germline variants leading to a certain condition. This is because ClinVar labels as ‘pathogenic’ / ‘likely pathogenic’ variants that are reported to be oncogenic in the somatic cells (see the figure above). This is a minority of the ClinVar entries, but we encourage to check the details of the entry in the original ClinVar resource by clicking the link provided in the MTBP report. The other source of information about variants pathogenicity employed by the MTBP pipeline is BRCA Exchange, which at present only includes information about germline variants.

In the left panel, we show an example of variant that is described as pathogenic in ClinVar and is mostly related to somatic events. On detail, KRAS p.12 G/V in germline is involved in rasopathy, but most of the knowledge about the variant is related to its oncogenic effect in the somatic cells of different tumor types. In the right panel, we show an example of a pathogenic variant (MSH6 p.1087 P/X) which is linked to different conditions when occurs in germline. Of note, most of the entries in ClinVar correspond to variants whose effect is reported only in germline events.

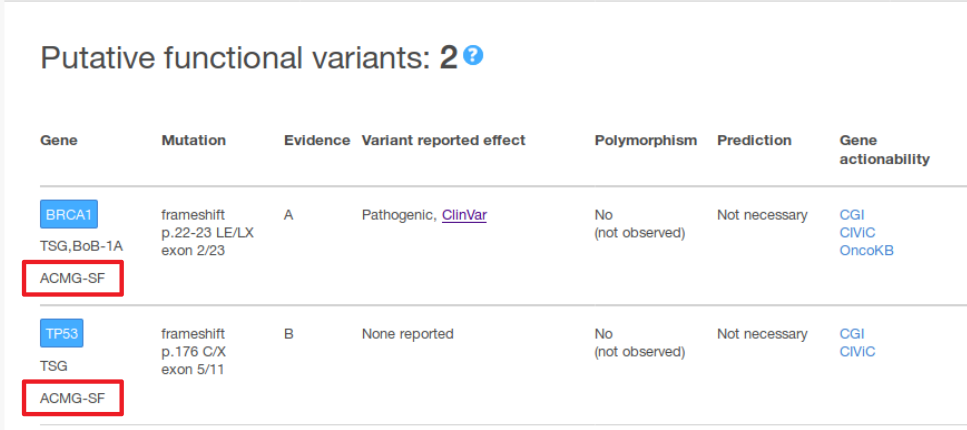

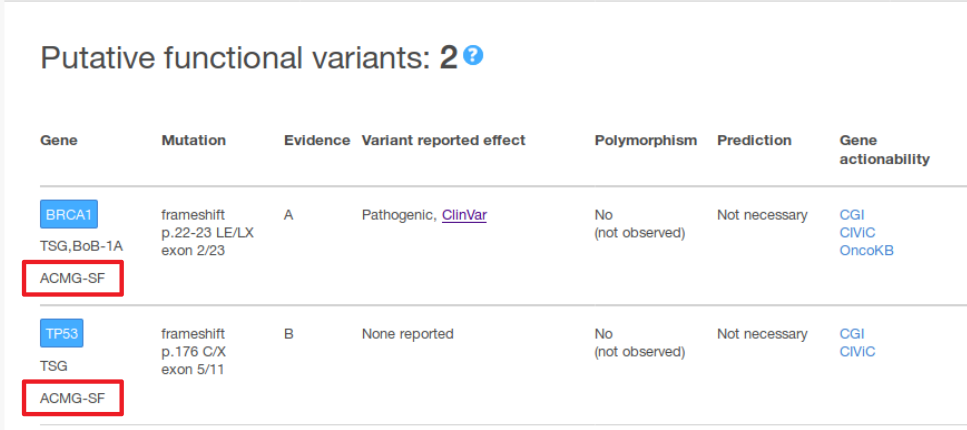

In addition, the current MTBP version includes in the report a label to indicate whether a gene is among those in which the observation of pathogenic germline variants are recommended by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) to be reported as incidental findings (see image below).

Genes whose variants are recommended to report as secondary findings by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics if found germline and considered pathogenic are flagged with the ACMG-SF label.

In the above figure, PTEN p.68 Y/H variant is found in the CCE panel, germline call (VAF=57%). This variant is described as Pathogenic/Likely Pathogenic by ClinVar (which makes the variant to be pre-classified as putative functional, evidence A, in our report). By clicking in that entry, the original ClinVar entry will be opened in a new browser tab (shown in the figure above: an interpretation agreed across several ClinVar submitters --see the two stars on top-- for the germline variant causing three different conditions --as last reviewed in June 13, 2018--).

Of note, not all the variants labeled as pathogenic (or likely pathogenic) correspond to germline variants leading to a certain condition. This is because ClinVar labels as ‘pathogenic’ / ‘likely pathogenic’ variants that are reported to be oncogenic in the somatic cells (see the figure above). This is a minority of the ClinVar entries, but we encourage to check the details of the entry in the original ClinVar resource by clicking the link provided in the MTBP report. The other source of information about variants pathogenicity employed by the MTBP pipeline is BRCA Exchange, which at present only includes information about germline variants.

In the left panel, we show an example of variant that is described as pathogenic in ClinVar and is mostly related to somatic events. On detail, KRAS p.12 G/V in germline is involved in rasopathy, but most of the knowledge about the variant is related to its oncogenic effect in the somatic cells of different tumor types. In the right panel, we show an example of a pathogenic variant (MSH6 p.1087 P/X) which is linked to different conditions when occurs in germline. Of note, most of the entries in ClinVar correspond to variants whose effect is reported only in germline events.

In addition, the current MTBP version includes in the report a label to indicate whether a gene is among those in which the observation of pathogenic germline variants are recommended by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) to be reported as incidental findings (see image below).

Genes whose variants are recommended to report as secondary findings by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics if found germline and considered pathogenic are flagged with the ACMG-SF label.